Learning to Follow His Path: Joe Bernstein ’93

The whole Bernstein family felt connected to Miquon School from the very beginning. Joe Bernstein ’93, was the middle son and he and his brothers all attended—David, was 4½ years older and Will, 5 years younger. His parents were both Philadelphia judges who were strong believers in social justice and Progressive education. The family lived in an area of Mt. Airy among several families that felt the same way.

“I thrived in the environment at Miquon that pushed me to be the best I could be, without the realization that I was trying,” Bernstein says. “There was the right level of creative structure, meaning that there was learning and play with a healthy dash of personal responsibility.”

Bernstein recounts many stories of his time at Miquon, with a few standouts:

Life lessons

At age 10 or 11, in Tony Hughes’s science room, Bernstein remembers working in a sandbox with a Bunsen burner and heating brightly colored crayons until they liquefied. Once the waxy liquid was melted and bubbling, the students poured it into the sand while it was still burning, delighting in the shimmering colors of the flames.

“It was incredible,” he says. “Tony was informative and engaging and the experiment was serious—no one played around—but it wasn’t solemn. It was age-appropriate, and you knew on some level that he was giving us freedom and authority to do something that was cool as well as being a real learning experience. We felt proud of what we were doing, and it blurred the line between learning and play.”

Something so simple taught the students several things they would keep with them forever: Making the discovery that matter changes forms when it is heated. Learning how colors mix and change at the same time. Experimentation. Safety instruction. Science is cool!

“We were encouraged to dig deeper and realize that things aren’t always what they seem,” he explains. “We changed the physical attributes of something to see what it would become. And we realized that we were considered more ‘adult’ in the Miquon environment because we were allowed to use this childish object for scientific purposes. We were no longer Kindergartners who used crayons only to try and color inside the lines.”

Daily lessons were found everywhere at Miquon, Bernstein recalls. Walking along the creek, turning over rocks and finding salamanders became another science lesson later in the day. The patterns made by fallen leaves, shimmering golden in the sunlight, were later discussed in an art or math class.

The chickens that 6th graders adopted taught other lessons. “We’d have to collect the eggs and bring them to the kitchen,” said Bernstein. “We had the privilege of taking those chickens for walks and showing them off to the younger students who were not yet given that level of responsibility.”

Bernstein realizes now that those types of lessons were incorporated into everything he was asked to do there. “it all encouraged us to be joyful, inquisitive. Our intellectual curiosity was piqued until we got to the point that we were interested in everything!”

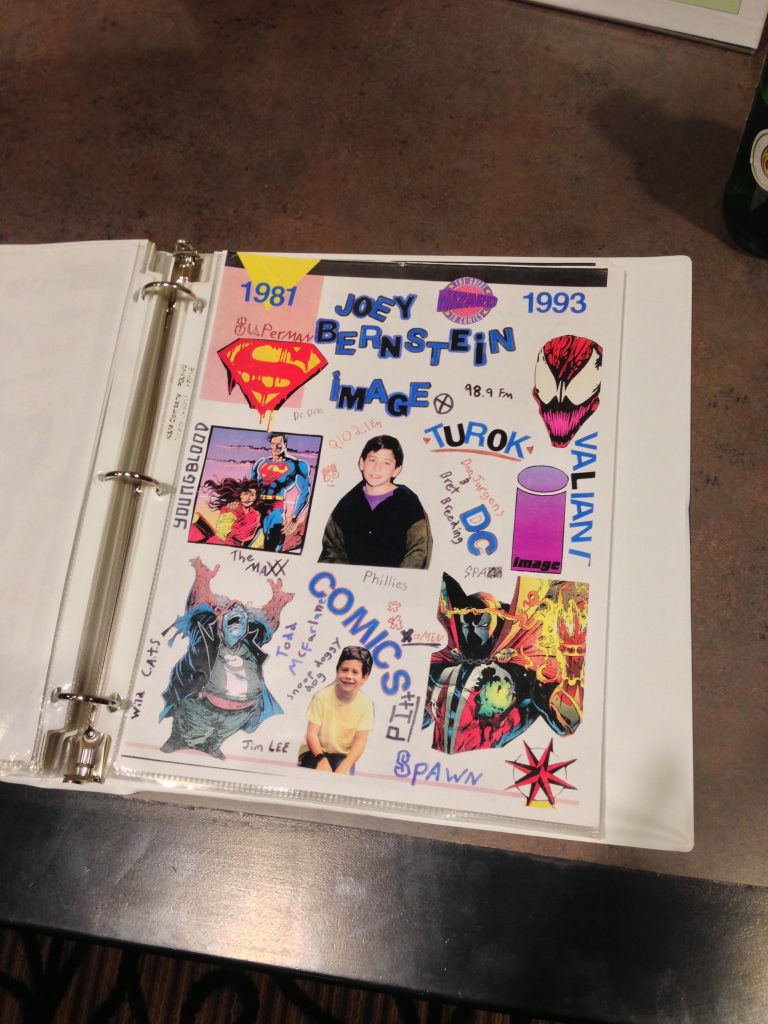

Joe’s Miquon yearbook page, circa 1993

Joe’s Miquon yearbook page, circa 1993After graduating, Bernstein attended Masterman School for a few years and finished high school at Friends Select in Philadelphia.

“Masterman was fine and I felt connected to Friends, with its Quaker values and social justice elements, but my most critical educational experience—and enjoyable—was Miquon, hands-down,” he says.

When the lessons sink in

Bernstein remembers one portion of his Miquon experience that he has only more recently begun to understand.

“I know now that the lectures I got from Lynn Hughes (married to Tony and Bernstein’s fifth and sixth grade teacher) were lessons she was using to tell me I am a natural leader,” he explains. “She was saying, ‘You will get this, but maybe not right now,’ and it wasn’t what I wanted to hear then, but it sunk in.

“She was going out of her way to make me a more well-rounded person who could be compassionate and caring.”

Today, Bernstein is a partner in a property management firm in Philadelphia. He is aware that his chosen field can be challenging and requires a certain awareness. “Miquon taught me a level of fairness and justice that makes playing in challenging arenas worthwhile and knowledge that I can outwork anyone if I just buckle down.”

The level of self-responsibility instilled at Miquon was greatest, in his opinion, because report cards didn’t come with letter grades, lessening the sense of competition and comparison between the students. “You wanted the satisfaction of having the answer when you were called on. You didn’t need to get all As to please your parents or teachers. That level of self-responsibility has propelled many of my successes because it means there are no shortcuts, and [shortcuts] don’t lead to the right answer anyway. It’s a marathon, not a sprint,” he adds.

Bernstein’s marathon led him to Boston University, where he majored in political science and entertained thoughts of law school. He ultimately chose real estate because of his innate entrepreneurial spirit and excitement he felt around contracts and negotiating. For a time after graduation, he worked for a Philadelphia city councilman where he says he “learned how to help people with anything and everything from the difficult to the mundane.” Then he worked on John Kerry’s presidential campaign in 2004, and soon was hired to do property management for a large firm in Center City.

“I told them when I was hired that I need to do things the right way, even if that’s the long way,” he says. “I’ve always done everything that way. I’m very goal-oriented, and that’s a foundation that was poured at Miquon.”

Bernstein found and married someone who embraces the Miquon philosophy, even though she did not attend the school. He and Tegan, who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and was chosen by Michelle Obama to help design her White House garden, have a 2½-year-old daughter, Azalea, whom they hope to send to Miquon when she is old enough.

“I was raised as a Unitarian, which, mixed with my Miquon background, stressed the inherent worth and dignity of all people, diversity, respect … we live our life with many of those foundational ideas and we’re passing them down to our daughter,” Bernstein says.

Miquon was a lot like his parents, who didn’t tell him what to do, but told him what they thought and allowed him to internalize that and come up with his own realization. “We were never put in a box, but they (Miquon) would sprinkle crumbs that would help you follow your path,” he says. “But it was still your path.”