Looking Back 50 Years: A Lynn Hughes Retrospective

More than 50 years ago, Lynn Hughes first set foot on this campus — said by some to be passing through the Miquon Day Camp as a staffer for just one season before attending to the adventures beyond that called her. A few years later, it became apparent she would be here for more than just a moment.

With Lynn being a lover and player of folk music, it is not surprising that the story of how she first came to Miquon reads a bit like legend.

It was 1967. Miquon was host to a “Focus on Citizenship” social studies seminar that year, sponsored by The Philadelphia Foundation. The agenda for the day included sessions on “Private Values and Public Commitment, Demands of the New Age,” and “Possibilities for Citizenship Education” hosted in the “Large Red L Building,” or what is now known as the Clisby Library.

During this era, Miquon was known throughout Philadelphia for its pioneering work in math education. Miquon was participating in an elementary mathematics teacher training program with several schools that no longer exist — Muhr School and Ferguson School among them. Lynn volunteered to help with activities for Don Rasmussen (Miquon principal, 1955-65) and his Durham Learning Center, which used Miquon’s facilities to bring inner city kids out to “the country” to do math on Saturday mornings and swim in the afternoons.

During this era, Miquon was known throughout Philadelphia for its pioneering work in math education. Miquon was participating in an elementary mathematics teacher training program with several schools that no longer exist — Muhr School and Ferguson School among them. Lynn volunteered to help with activities for Don Rasmussen (Miquon principal, 1955-65) and his Durham Learning Center, which used Miquon’s facilities to bring inner city kids out to “the country” to do math on Saturday mornings and swim in the afternoons.

Around the same time, Lynn embarked on her teaching career in the very same spot. She was brought on by Sam Stewart (Miquon principal, 1966-70) as a second and third grade teaching assistant to Esther Soler — one of many teachers who had been forced out of the Philadelphia public school system during the McCarthy era for refusing to sign a loyalty oath.

Around the same time, Lynn embarked on her teaching career in the very same spot. She was brought on by Sam Stewart (Miquon principal, 1966-70) as a second and third grade teaching assistant to Esther Soler — one of many teachers who had been forced out of the Philadelphia public school system during the McCarthy era for refusing to sign a loyalty oath.

Described by many as a person with a sharp intellect and quick, hilarious wit, Lynn got caught up almost immediately. She immersed herself in reading materials, cooperative work with colleagues at school and elsewhere, and professional development wherever she could — attending conferences and eventually becoming the editor of the Association of Teachers of Mathematics of Philadelphia and Vicinity newsletter for 12 years.

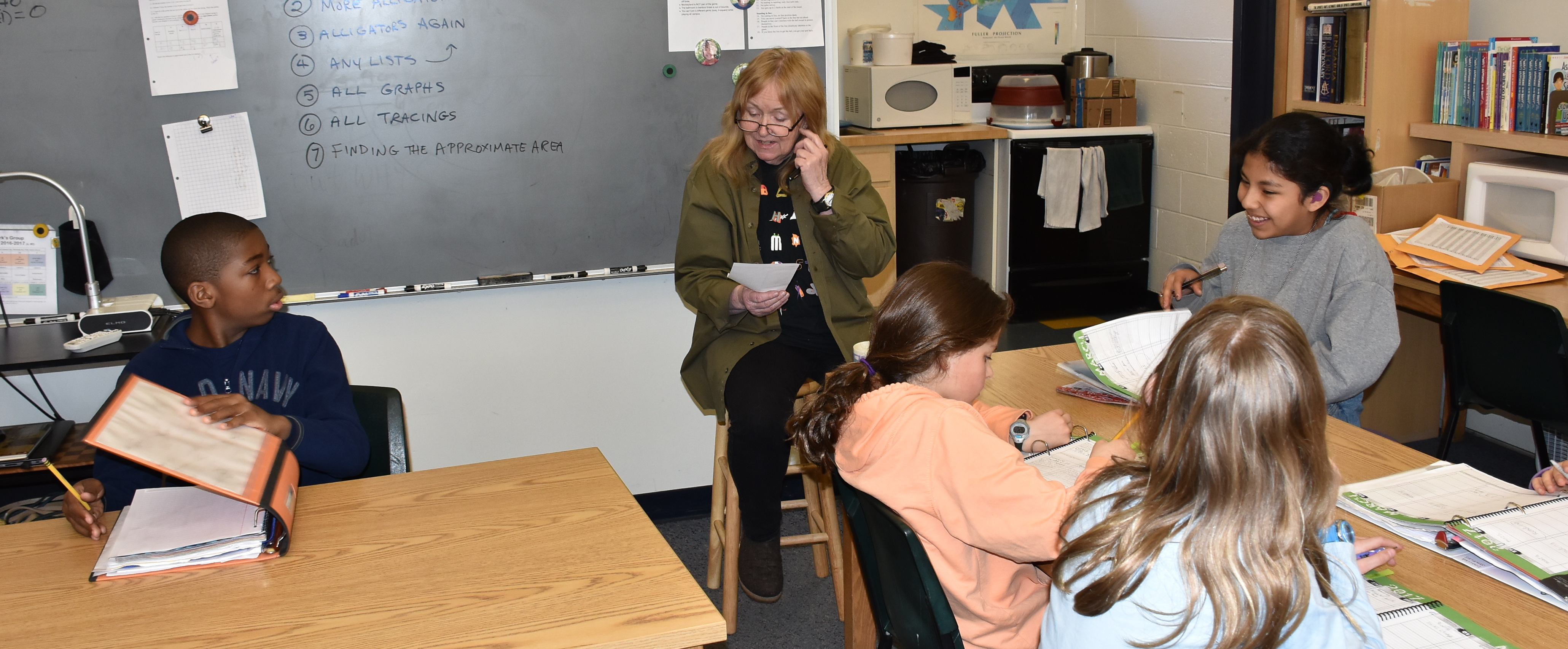

In 1968, Stewart assigned Lynn her own classroom, where she worked tirelessly to meet students where they were and cultivate each individual child’s innate desire and abilities to learn. Because Miquon did not receive any state funding for published resources or commercially-produced materials back then, the staff spent ample time creating just about all of their text, worksheets, and objects for curricular use. Using this challenge to her advantage, Lynn tailored her teaching materials to individual students to ensure they supported the kind of learning environment she was trying to create. “I had to think carefully about the content and the structure,” she says.

Influenced at the outset by the Progressive craft of Rasmussen and Soler, it was not long before Lynn became a fifth and sixth grade teacher, and settled into her own teaching style.

First and foremost, Lynn Hughes will tell you she puts the child first, teaching “to the student,” not the subject. Arabella Pope, a Miquon colleague of Lynn’s for many years, explains: “She seems to know exactly what individual kids need–both academically and emotionally. She knows every child in her classroom very well and how it fits into what children do at their age.”

First and foremost, Lynn Hughes will tell you she puts the child first, teaching “to the student,” not the subject. Arabella Pope, a Miquon colleague of Lynn’s for many years, explains: “She seems to know exactly what individual kids need–both academically and emotionally. She knows every child in her classroom very well and how it fits into what children do at their age.”

Above all, Lynn offers respect to children, imparting a deep confidence that they each have the ability to reach, grow, develop their own passions, and become the very best version of themselves. “In Lynn’s view of children, there are no limits to what they can do or who they can become,” says Susannah Wolf, the school’s current principal and a Miquon graduate from 1981.

A part of this intrinsic respect for children means Lynn always considers what students are thinking and feeling. One alumni parent describes a memory of a very animated student asking Lynn a question, and then seeing the child wait for a seemingly endless amount of time. Becoming impatient, the student said, “Well? What do you think?” to which Lynn replied, “Be patient, I’m trying to find a way to say yes,” a sentiment she’d adopted from Miquon teacher Cubby Weil who had said it first.

“I have certainly borrowed the [Cubby’s] answer because it seems like the right kind of response to things that children initiate,” Lynn explains.

In addition to her child-centric approach, Lynn is known for her innovative integrated curriculum–the idea that a social studies unit exploring westward expansion is the perfect opportunity for mathematics (What’s the diameter of the covered wagon wheels? How does one calculate rate and distance the settlers traveled each day?) or that a deep understanding of Irish immigration presents ample material for literature, language, and music.

While Lynn and Miquon have been teaching this way since the beginning, the model is only now taking root with a wider audience of educators. The Spring 2017 issue of Independent School magazine calls for schools to think differently about their educational models in order to flourish in a future that is changing rapidly. In his article, “Education in the Age of Innovation,” John Kao discusses “the old days” of learning shifting away from “a fixed container with firm boundaries to a blending learning environment.”

Lynn explains: “Learning is best when it is highly integrated across nominal curricular areas. When we can embark on a study that incorporates history, literature, music, mathematics, art, science, games . . . it’s real and it’s involving. We don’t live in a compartmentalized world.”

But she doesn’t take this approach only because it is Progressive or even because it just makes sense. She takes this approach because it is her passion.

“I love teaching disparate things that can be woven together into a coherent whole,” she says.

Fast forward 20 years. In 1987 the Clisby Library was created after renovating “Lynn’s room,” teacher salaries were raised to be on par with other independent schools, and a celebration was held at Shelly Ridge honoring Lynn for her “20 years of dedicated teaching at The Miquon School.”

Much like the present day, Lynn’s craft and voice permeated the Miquon program. She was outspoken at staff meetings, suggesting assigning the responsibility for each weekly assembly to different classroom groups, running a minicourse on rounds, partners, songs, and harmony, and advocating for looking at issues on the basis of each individual child.

According to one alumni parent who also served on the Miquon School Board of Directors with Lynn, “You felt her presence, always. She didn’t say much, but when she spoke, you listened.”

Today one could argue that Lynn’s teaching philosophy is inextricably linked to that of the school; the two have been together and influencing each other for half a century. A quick read of the school’s nine published tenets immediately reflect Lynn’s own — the ideas that children have innate curiosity and a desire to learn, that children must initiate and discover new ideas for themselves and see their own progress, that learning to think is more important than learning any particular subject matter, and that the support of one’s peer group creates a safe learning space. Not surprisingly, Lynn was the co-author of these tenets, along with board member Craig SanPietro.

Today one could argue that Lynn’s teaching philosophy is inextricably linked to that of the school; the two have been together and influencing each other for half a century. A quick read of the school’s nine published tenets immediately reflect Lynn’s own — the ideas that children have innate curiosity and a desire to learn, that children must initiate and discover new ideas for themselves and see their own progress, that learning to think is more important than learning any particular subject matter, and that the support of one’s peer group creates a safe learning space. Not surprisingly, Lynn was the co-author of these tenets, along with board member Craig SanPietro.

It therefore follows that, despite her pending retirement this June, a teacher who has shaped hundreds of children over the years will continue to do so in the way she has shaped Miquon as an institution. And while there have been some changes, including the challenges and opportunities brought on by digital technology, the increasingly valuable role of assistants (who now make more than $25/week), and the longer hours asked of teachers and children alike — Lynn reassures us that the school is fundamentally the same in ways that really matter.”

When asked what she will take with her, Lynn cites the moments for which all teachers strive: the “almost palpable” joy when a child achieves something new, something previously unattainable. Witnessing that magic first hand is a payoff that far exceeds any monetary compensation; it is the measure of any person’s career at a teacher. It is what motivates us all — those who teach, those who learn, and those who care for us — here at Miquon.

So here’s to you, Lynn Hughes, and the legacy you leave behind you in our woods.