The Struggle to Play

By Diane Webber, fifth grade teacher

This summer I visited the Canadian Museum of Civilization, just outside of Ottawa in Gatineau, Quebec. I was struck by its architecture and the fascinating cross-cultural content that it offers. Most of all, however, I was impressed by the ways in which the museum demonstrates an understanding of human cognitive nature. Humans learn through play. As one would expect, the museum had data, perspectives and questions about history to communicate. Everything about its design respected the fact that people, by nature, are most likely to absorb ideas when invited to play with them. Certainly, this was true in the “children’s museum” portion, where there was abundant opportunity to play — building, playing with puppets and dollhouses, creating and climbing. There were multiple scenes (restaurants, stores, etc.) that encouraged detailed role play. This, while especially well done there, is the kind of thing we have come to expect in a children’s museum.

This summer I visited the Canadian Museum of Civilization, just outside of Ottawa in Gatineau, Quebec. I was struck by its architecture and the fascinating cross-cultural content that it offers. Most of all, however, I was impressed by the ways in which the museum demonstrates an understanding of human cognitive nature. Humans learn through play. As one would expect, the museum had data, perspectives and questions about history to communicate. Everything about its design respected the fact that people, by nature, are most likely to absorb ideas when invited to play with them. Certainly, this was true in the “children’s museum” portion, where there was abundant opportunity to play — building, playing with puppets and dollhouses, creating and climbing. There were multiple scenes (restaurants, stores, etc.) that encouraged detailed role play. This, while especially well done there, is the kind of thing we have come to expect in a children’s museum.

The museum carries this concept further though, much further. In most sections, people large and small literally stroll through the history of civilization, and are encouraged to “play the part.” Informational panels are not the primary source of information, though there were some of those. Instead, one looks up and sees the “sky” above, and is surrounded by the variety of sights and sounds of the time and place. When we play, we experience with multiple senses simultaneously, we sense a different set of rules, different space, a different concept of time. The Canadian Museum of Civilization recognizes this and fulfills that need beautifully. Sometimes to the chagrin of my family, I have a long history of museum-mania. Having visited more museums than some find necessary (or healthy), I assure you this recognition of play as central to learning for all ages is a rare find in such institutions. Sadly, it’s a rare find in schools as well.

In 1938, Dutch historian, Johan Huizinga, famously described the nature of play and its primary significance in culture. He named five characteristics: 1) play is free and voluntary, and people set the terms and timing of their involvement; 2) play has no material consequences, nothing gained or lost; 3) play is different from daily tasks — exotic rules, space, time, costume and equipment set it aside; 4) play both honors rules and order, and encourages transgression and disorder and 5) play promotes banding together.

How do we at Miquon encourage play — in all its aspects — to be a large part of children’s lives? Much of what we do in the classroom – all the way up and through the Fifth and Sixth Grade, contains flexible thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, communication about the rules and boundaries as they develop and skill development based on young people independently experimenting until they find the “just right” level of challenge. Still, in the older groups especially, these characteristics of play are joined by the very important free and voluntary aspects typically only at choice time.

This year I introduced “play” as our social studies theme for the fall, in part because I wanted to see if free and voluntary play could be more an attribute of classroom life — outside of choice time. The most significant shift in routine was the introduction of “make and play” time in which the fifth graders sought inspiration from physical materials, books, online or people to create and use play items. Children could engage in a project on their own terms, and disengage at will. Materials were not “precious,” and could therefore be used for risky endeavors. Children are singularly engaged in this part of their day, and have been from the beginning. The level of focus, productivity, communication, independence in problem-solving and collaboration is spectacular! I knew it was free and voluntary when it simply spilled over into and through choice time.

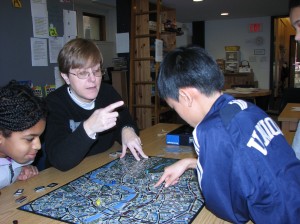

I have tried to learn from this, to spot other activities that could readily be as open-ended, as inviting of voluntary investment. I have found some success with board and card games, writing, even a grammar game. Yet, even as we do those things, we are wistful as we listen together to Swallows and Amazons, the 1930s semi-autobiographical novel by Arthur Ransome in which children spend their days and nights fully at play. Play is the serious work of these children. The story drips with every element of play that Huizinga described many years ago, and we imagine ourselves living in that kind of learning bliss. We know that play is the key to learning, and at Miquon we continue to imagine ways to bring that more fully to fruition.

I have tried to learn from this, to spot other activities that could readily be as open-ended, as inviting of voluntary investment. I have found some success with board and card games, writing, even a grammar game. Yet, even as we do those things, we are wistful as we listen together to Swallows and Amazons, the 1930s semi-autobiographical novel by Arthur Ransome in which children spend their days and nights fully at play. Play is the serious work of these children. The story drips with every element of play that Huizinga described many years ago, and we imagine ourselves living in that kind of learning bliss. We know that play is the key to learning, and at Miquon we continue to imagine ways to bring that more fully to fruition.

To learn more about work and play in Diane and Jeri Bond-Whatley’s fifth grade, view their blog.