Emergent curriculum stimulates students’ desire to learn

Children are born curious and they love to learn.

When children become school-age students, they bring their curiosity and intense personal interests into the classroom. Their perspectives, prior experiences, and cultural backgrounds can have a huge influence on the vibrancy of their learning and relevancy of their work. Moreover, recent brain development research shows that achievement improves when learners are given time to pursue topics that are important to them.

What is Emergent Curriculum?

Allowing space and flexibility for learners’ interests, questions, and ideas is often referred to as an Emergent Curriculum. When curriculum is emergent, it is a co-creation between teachers and students, something that develops over time and through shared questioning and exploration.

Discovery activities where children wonder “What if or how can we . . . ?” and inquiry projects that ask “What do you know already, and what more would you like to learn?” serve as guiding questions for exploration. Teachers then very intentionally structure the unit to include grade-level skills and concepts.

“Although the activities, lessons, and projects will vary from year to year,” suggests Lynn Hughes, fifth and sixth grade teacher at The Miquon School, “learning goals remain the same.”

In other words, although different topics may emerge each year based on student interests, teachers take care to include a specific learning scope and sequence in the areas of language arts, mathematics, and social studies.

Giving students the chance to pursue their interests not only paves the way for increased enthusiasm about learning — it also presents a relevant and meaningful canvas for children to practice critical math and reading skills.

At Miquon, children take on big, real work and make it their own.

Recently at The Miquon School, first graders were very keen on making food. This interest persisted in the form of inedible foodstuffs made of paper, play dough, and more — as well as impromptu signage throughout the classroom advertising goods.

The teachers saw this passion as an opportunity to build on their students’ food-related curiosity with a new unit that would touch on many first-grade level skills and concepts, including the four pillars of literacy (speaking, listening, reading, and writing) and mathematics (addition and subtraction).

“When asked if they would like to make their own real restaurant, the children’s response was an enthusiastic one,” explained Ben Coleman, first grade teacher.

What emerged from this passion was a cross-curricular study, including math, measuring, spatial work, number sense, writing, planning, and the science of baking and cooking.

As plans began to form, the group used the guiding question, “What do people do in restaurants?” to focus their research.

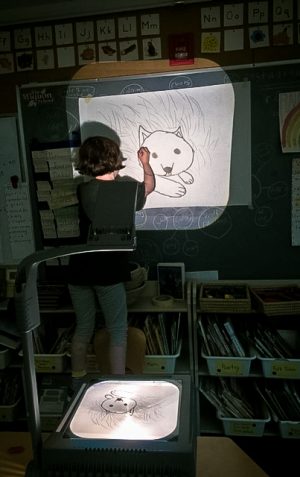

It was agreed the restaurant would be named the Wolves’ Den, and several children prepared large-scale paintings for the space. They made line drawings on small pieces of paper, which were then projected onto a large canvas. They then traced their blown-up drawings.

“Children love a very straightforward, visual process. In this case, ours involved light, shadow, and lens to transform their original image,” said Coleman.

Next the children determined that sticks could serve as frames for the art. Several children immediately set off to the Miquon woods to gather sticks as the teachers helped them along with their plans.

A teacher asked, “How will you know if the branches are the right length for the painting you are framing?”

“We can measure the sides of the painting,” a child responded.

Again the teacher questioned, “Wait! How will you know how long each stick is?”

Another child answered: “We can bring rulers!”

Next the first graders estimated they would have 50 patrons on the day of operation.

One child posed the question, “What will happen if all 50 people come at once?”

Following this, the children tried to split 50 into three groups using Unifix cubes. They worked through the math to “make it come out even,” but soon figured out the split would have be two groups of 17 and one group of 16.

When the restaurant opened, the children were the chefs, dishwashers, and wait staff all working to prepare and serve the various pizzas available on the menu. Servers took orders on cards that were easy for first graders to read and user-friendly for cashiers calculating the cost of each meal.

The following day, the children counted the earnings, tallied the most popular menu items, and used graphing activities to portray results.

With an emergent curriculum, teachers work to integrate grade-level appropriate skills and concepts into the lesson. As with the first graders at Miquon, the restaurant study not only presented an opportunity for children to participate enthusiastically in their learning, it was also a chance for students to practice their newly acquired skills. Through the study, children work on first grade benchmarks for speaking clearly (in welcoming and seating guests at tables), listening and writing using letter sounds (when taking food orders), reading using sight words (reading the orders), and adding and subtracting (the cost of the meal) using place value.

“It is both the culmination and the application of all the skills they have learned. And yet it is much more meaningful and memorable than a worksheet because their investment in it,” shares Miquon Language Arts Coordinator Rossana Zapf.

Be it an exploration of woodland animals, urban habitats or transportation systems, emergent curriculum provides an opportunity for children to purposefully and enthusiastically apply their grade-level skills in a manner that is meaningful to them.