The View from the Break-out Room

This article has been cross posted. Go to Diane and Jeri’s full blog site.

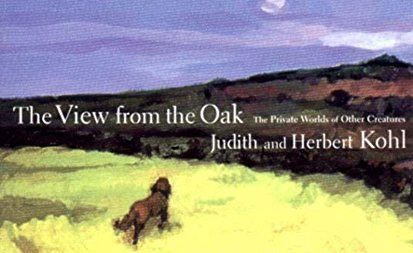

Our story (read aloud) time in the break-out room this year has been a bit unusual so far. Rather than beginning the year with a novel — often a classic — the material was tied more specifically to our thematic study, and we read a significant number of biographies of naturalists. Typically, they were from the picture book genre, which is not to say they were simple, but rather brief enough to complete in a few sittings. When we finished those, we read stories from In the Beginning: Creation Stories from Around the World, again connected to our theme. This well-regarded collection of stories, retold by Virginia Hamilton, presents the stories and their cultural contexts. This read aloud complemented well the learning we were doing about worldview prior to the work of Charles Darwin, helping us to develop context for that work. For the last couple of weeks and for the next couple of weeks to come, we are reading The View from the Oak: The Private Worlds of Other Creatures, by Judith and Herbert Kohl. This marks the third consecutive unusual read aloud choice!

This work of nonfiction, which won the National Book Award for Children’s Literature, is a work of ethology. Ethology is the scientific and objective study of animal behavior, with a focus on behavior under natural conditions, and viewing behavior as an evolutionarily adaptive trait. It explores the ways in which creatures experience space and time and the ways in which they communicate with each other. In short, and to use the term in the book — it describes their umwelts. Please, take a minute and ask your child what that word means. It’s critical to our reading.

The View from the Oak describes just one fascinating mini-experiment or experience after another, we are keeping a list of those that interest us and tossing around the idea of having an “Umwelt Day” — a day of carrying out those experiments. We are also having many, many conversations, some of which extend into conversations at other points in the day, about the big ideas presented in the book. For example, this week we are veering toward a discussion of special relativity, perhaps a topic not typically found in a fifth or sixth grade curriculum.

Why would we read such a book to and with 10-12 year old children? It is indeed a special book that can reasonably address such complex ideas in a way appropriate to an audience this age. The book connects very concrete examples with much more abstract thinking, and this is precisely where these children are stationed developmentally. It also raises questions and leaves some answers open-ended. The ability to live more comfortably in such “gray” areas, to entertain seemingly contradictory ideas simultaneously, is also just becoming appropriate — and can be very exciting — to children at this age. The book deals with the worlds of animals, a topic generally interesting to children and seemingly particularly so to this group. Finally, the material openly encourages the reader to develop metacognition, an awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes. This is a hallmark of cognitive growth that we are actively supporting in fifth and sixth grade students.

Can every child in the group connect to all of these things fully? Of course not. Some are more than ready for the philosophical inquiry this book invites. Others are intrigued by it, and just dipping their toes in. Others are really interested in the concrete information about animal experience and encounter the bigger ideas largely through that lens. We work to meet that range: 1) by making copies of the book available for children to read along; 2) by tying the ideas to our just begun Species Studies projects, in which each child will be attempting to describe the umwelt of a particular species; and 3) by planning a hands-on celebration/exploration of the ideas when we finish.

It is a lucky thing to teach children in a place where “unusual” reading choices are not perceived as negative, and where children can be developmentally “met” and stretched simultaneously.