Tiny Harvest

Put some seeds in your pocket

Feel the promise of what may come

after the winter has had its say

Know that this bounty was made possible

by the hunger of little ones

and the sweet allure that drew them near

Nature’s gifts are on full display at Miquon. This fall, students explored the cornucopia around them through experiences designed to engage the senses. They touched, smelled and tasted herbs from the garden; baked butternut squash and fried eggplants; they cut down tall sunflowers, rubbed the dried petals away and then listened to the delightful “ting” sound that a single clean seed makes when it drops into the bottom of a metal bowl.

Each of these experiences were small, but important, parts of a broader study on plant anatomy, plant life cycles and adaptation. Second, third and fourth grade students investigated these topics with the purpose of developing a greater appreciation for the diversity of life flourishing on our campus and a more nuanced understanding of the ecological cycles that sustain us.

|

| Preparing butternut squash for soup and baking.Recipes can be found here. |

|

| Butternut squash and apples before blending. |

We started by preparing the plants that were prime for picking! Last spring, students worked hard to harvest bamboo from the bamboo forest and built new beds for the garden. Their labors were rewarded when they returned to find an abundance of ripe butternut squash and eggplants. In preparing these foods, students spent time noticing the vegetables in ways that they hadn’t before. As we peeled, seeded and chopped, children remarked on the texture of the skins, the changing layers inside and what exactly constitutes a bite sized piece. They also hypothesized about which animals had visited the garden and looked for clues in the bite marks of nibbled parts. Many students were surprised by the large number of seeds produced by just one squash and began working through computations aloud as they estimated how many new plants could be produced from the one seed that had grown into a mature plant in our garden.

|

| Separating sunflower seeds from the flower. |

|

| Cleaning sunflower seeds before boiling and roasting. |

|

| Roasted sunflower seeds, ready to eat!Students collected and transported seeds in these funorigami cups. They’re really useful and easy to make! |

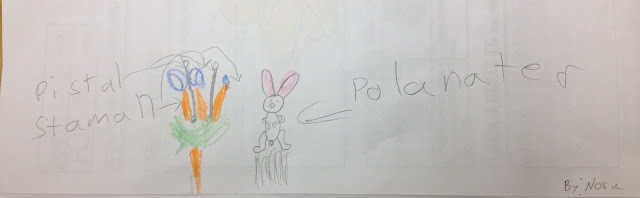

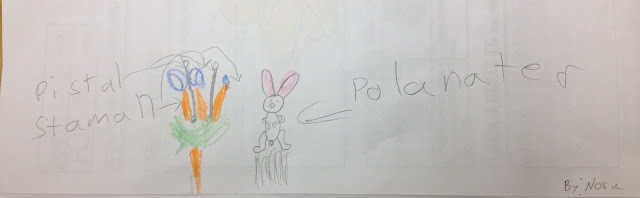

The questions raised while cooking and conversing were explored more deeply through lessons on plant anatomy and life cycles. Students watched explanatory videos from the sites Brainpop and BrainpopJr before using microscopes to examine pistils, stamens and petals from roses. We later reviewed the vocabulary associated with pollination and fertilization through games and creative drawings.

|

| After studying plant anatomy and fertilization, students were asked to creatively design their own flower that attracted a specific pollinator. I’m a little partial towards bunnies, so I thought I’d share this adorable “carrot flower.” |

|

| Students observing jewelweed flowers and seed pods. |

Outfitted with magnifying glasses, groups observed the wide variety of flower shapes and sizes on campus. (Just in case you’re wondering, butternut squash flowers seem to have the biggest stamens.) A few weeks later, we revisited these plants to witness the change from fertilized flowers to fruits. Two classes were downright enchanted with the spring-loaded seed pods of jewelweed (touch me nots) and joyfully spent the next few choice times triggering every pod within sight. Seed dispersal was also a favorite topic of discussion, particularly when it involved describing the intestinal journey (and relocation) of seeds after they are eaten by animals. The idea that plants often benefit from animals eating their fruits cast a new light on the deer scat found in the crab apple orchard.

|

| Radish seeds growing towards light. |

Students readily made connections between flower shapes and the pollinators that they attract, but needed more direct instruction to begin unraveling how adaptation relates to the survival of a species. Second and third grade students experimented with radish seeds to find out if radish plants have the ability to grow or bend towards light. Our results were twofold–first, that not all seeds growing under the same conditions will sprout, and second, that most radish seedlings do indeed bend toward light. We discussed the potential advantages of having this adaptation and threw around the fancy word “phototropism” with flourish.

After reading activities focused on identifying the adaptations of different animals, we began to frame adaptations as “superpowers” or special features that help living things survive in the context of their environment. Being familiar with this concept is critical to helping students connect structures to functions. It also lays evidence-based groundwork for later studies about natural selection and evolution, unifying themes in biology.

|

| Students visited different “adaptation stations” to learn moreabout the special structural features of different animals. |

(If you’re interested in finding out more about age appropriate curricular sequencing and building science knowledge, I highly recommend browsing through the National Science Digital Literacy Maps. A sample page describing the understandings associated with natural selection can be found here.)